The Statue in the Cave

Large Language Models can't even handle poop science. How are they supposed to help us create super-intelligent AI?

I swear to god, the next time someone sends me a link to a ChatGPT “analysis” of one of my articles, there’s going to be an unfortunate mixup in my postal logistics-handling spreadsheets, such that all the fecal samples which are supposed to come to my lab that week will instead wind up in that person’s mailbox by mistake.

(Kidding, obviously; I would never let good poop go to waste like that.)

Jokes aside, it’s worth talking about why—even though it’s just one of the many things current “AI” models are bad at—using them to try and understand the human gut microbiome is a uniquely terrible idea. And, at the risk of making a habit out of putting people on blast for relatively minor offenses, a recent example provides a good jumping-off point for the discussion.

A while after I put up the ALS hypothesis post, a reader reached out explaining that the disease runs in his family, although it appears to have spared him so far. So we sequenced his gut microbiome, and did the same for his relatives with ALS. I’m still combing through the data, but I sent him a copy of the big ol’ table reporting the relative abundances of all the microbes in his and his family’s guts, along with the same data from the participants in my ongoing cholesterol/coprostanol study for comparison (They’re not all exactly “healthy”, but to my knowledge none of them have ALS).

I don’t typically do this, because it’s a lot of information that most people can’t make heads or tails of, but he asked with an understandable sense of urgency, so I did some quick number-crunching and sent him my preliminary analysis along with the spreadsheet. Sure enough though, a day later I’ve got the dreaded link in my inbox, prefaced with the usual “Not sure if this is helpful, but I asked [LLM] and…”

Pessimistic, I clicked—like any good scientist should—hoping to be proven wrong. I was disappointed, but with the consolation prize that its attempt was so godawful that it broke me out of a month-long writer’s block.

The reader gave it good context around his family’s story, and fed in the URL of my ALS post along with the relative abundance spreadsheet. After a few overly florid lines of sympathetic therapy-speak and the requisite [I AM ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE, NOT A DOCTOR] disclaimer, it launches in with:

“The most distinct marker mentioned in Skolnick’s article (and supported by several studies, including Herzog et al) is that ALS patients often exhibit a “pro-inflammatory” gut microbiome characterized by a lack of Prevotella and an overabundance of Bacteroides.”

If you’ve read the ALS post, you might notice that this is what AI folks would call a “hallucination”, i.e. it’s dead fucking wrong from start to finish.1 Now, it’s the kind of thing you could half get away with if you were talking about practically any other piece of writing about the microbiome (or neuroscience, autoimmunity, metabolism, or any other aspect of health/disease for that matter), because “characterized by a pro-inflammatory state” is the most generally applicable catch-all excuse for a mechanistic insight imaginable. It could be said of practically any disease state, and—being applicable to everything—means next to nothing.

This is a pretty solid way for the LLM to fulfill the core directive sculpted into its architecture by a zillion hours of human feedback, which can be summarized as “string together words related to the query, in a sensible order, without saying anything logically inconsistent or objectively wrong”. Statistically, it took its best shot based on its training dataset—presumably missing the fact that it was supposed to read the linked article first and incorporate that into the “context window” that it uses to decide what to say.

And this is a great example of why the fundamental structure of an LLM is inherently ill-suited to synthesizing this kind of information.

Say there are six studies out there reporting elevated abundance of Bacteroides in COVID, and another three studies reporting reduced abundance of Bacteroides in COVID. If you ask an LLM about the microbiome’s role in COVID, more often than not it’ll tell you something like: “There’s substantial evidence indicating that Bacteroides is [elevated/depleted] in COVID,” picking one or the other somewhat randomly, because both of those are clearly acceptable words to slot into that spot in that sentence. It’ll pick “elevated” twice as often as “depleted”, because weighting your selections based on how often each one appears in sentences similar to the one you’re constructing is a pretty good way to produce sensible-sounding text; this context-dependent weighting is the basic essence of how all LLMs work.

What this means, though, is that it is not very likely to tell you “There’s conflicting evidence around the microbiome’s role in COVID, with some studies reporting an increase in Bacteroides, while others report a decrease”. Even if someone’s written a review article which says that, you’re not likely to get it as an answer from the LLM, because it looks like a minority viewpoint, relative to the nine individual articles it’s summarizing.

So it will come up with a sentence like “There’s substantial evidence indicating that Bacteroides is [elevated/depleted] in COVID, suggesting that this genus may [exacerbate/protect against] the condition”, because a thousand sentences of that general structure were in its training dataset. By incorporating a few words of context into the frequency weights, you can imagine how it would reliably pick between “exacerbate” and “protect against”, based on what it had already said, to construct something internally consistent: In the average sentence like the one above, “elevated” is almost never paired with “protect against”.

But this example makes it clear that there is nobody home, no understanding, and the appearance of understanding—of “object permanence”—is basically an elaborate parlor trick. The people who wrote the words which went into its training dataset, they had minds—and the shadows of these are encoded in their words. But in any kind of knowledge-work (and in science in particular) the precise meaning of a word and the nuances of the thing it refers to become critically important, such that any random variance you introduce to a text—i.e. the only thing that makes these models different from a search engine, which just displays the original text verbatim—makes it less useful.

The Importance of Discernment

What do you get when you take the average of five wrong answers and one right one?

This is the problem in a nutshell, because—while there’s an extraordinary amount of data out there on the microbiome in practically every disease—most of it is not very good. When you’ve got a situation like our Bacteriodes/COVID example, how do you know whether or not to trust a given study?

Well, were their sequencing methods based on shotgun metagenomics, or 16S? If the latter, right off the bat you’ve lost everything about eukaryotes like Candida, so if those play a role in your disease, there goes your signal. Still, there might be useful information in there, depending on what primers they used. If it was the standard out-of-the-box 27F that you get in a metagenomics kit like Oxford’s, you can basically throw the study in the trash; at least half your Bacteroides species aren’t even going to show up, along with most of the Actinomycetota (which contains good guys like Bifidobacterium and bad guys like Eggerthella).

If they DID use shotgun metagenomics, hey great—but before you trust the numbers, check their lysis and extraction protocols; did they validate with a mock community standard of known composition?

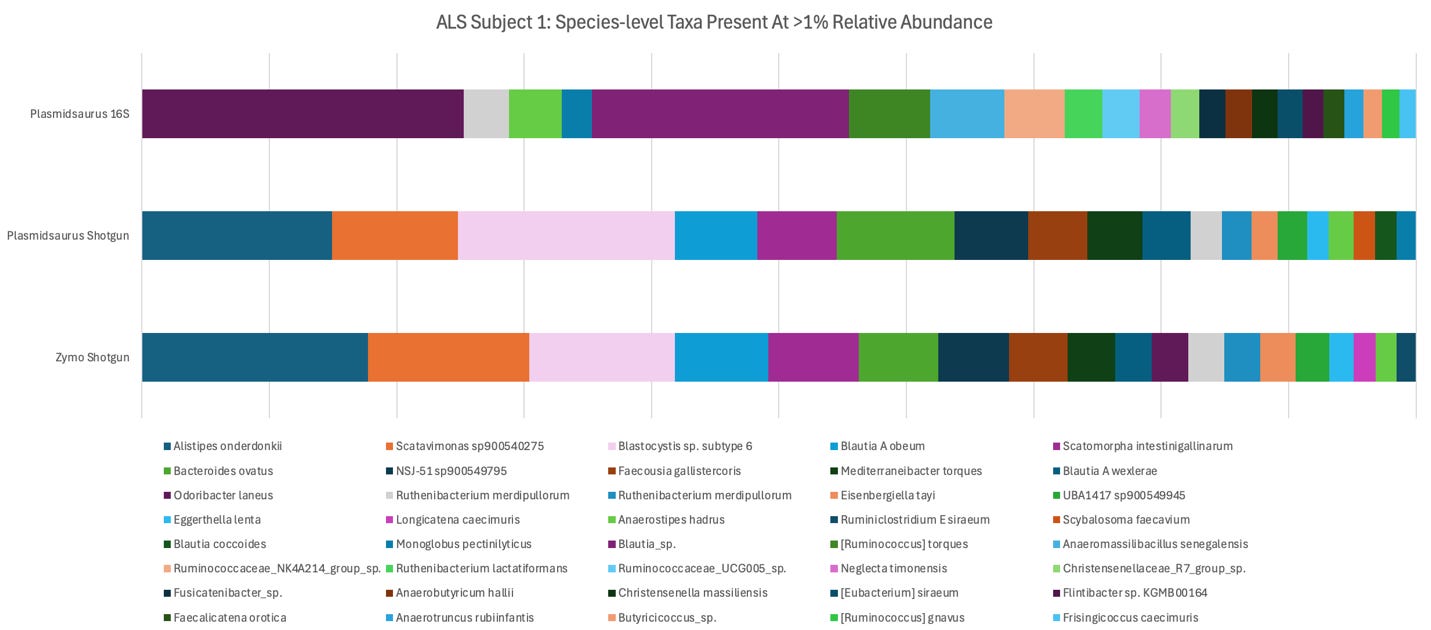

For a concrete example, have a look at the differences in community composition you get when you run the same sample through three different sequencing services:

Now, I had to do some major “flattening” (i.e. cutting out everything below 1% relative abundance) to even make this legible, but it demonstrates the above points nicely. That pink bar, Blastocystis, doesn’t show up in 16S, because it’s a eukaryote. Odoribacter laneus, which 16S says is 21% of this person’s microbiome, is actually closer to 1% by shotgun.

These are the kind of obstacles that stand in the way of our understanding these diseases, which is why LLMs—and even things like protein-folding models built on the same architecture—stand next to no chance of helping us overcome them.

The Cave

My wife and I went to the Bay Area “secular solstice” celebration a couple of weeks ago. It’s basically what you’d expect from the name: a few hundred friendly nerds getting together in a theater auditorium for something very much like a Christmas mass—readings, homilies, songs that everyone sings along to—except it’s things like “The Times They Are a-Changin’” instead of “O’ Little Town of Bethlehem”.

And it always feels good to get together and sing with a bunch of like-minded people, but I particularly love what it represents: the modern atheist movement growing out of its singular focus on intelligence, and into an appreciation for wisdom.

It’s a recognition that, while shaking off the chains of religion is all well and good (to the extent that faith has been used by the powerful to manipulate people for most of human history), the social glue it provides is an important part of human culture, and we’re poorer for its absence. That it’s worthwhile to get together to experience fellowship and community and awe, even if the supreme creator of the universe doesn’t command it.

So I was more than a little disconcerted by the extent to which the organizer’s reflections—the sermon, for lack of a better word—were focused on the existential risk posed by the supposedly impending emergence of superintelligent AI. The general message was that we’re living through a moment in human history much like the Cuban missile crisis, where this new technology threatens to wipe out our species unless we can come together and find a way to stop it.

The general outlook is grim, as best summarized in the title of a recent book speculating on the topic: “If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies”. The author, founder of the Machine Intelligence Research Institute Eliezer Yudkowski, was in attendance, and gave a brief speech about staying sane in spite of the end of the world. His words are clearly taken pretty seriously here. At one point, with the stage in full darkness to symbolize the longest night of the year, the organizer expressed the extent to which this fear had gripped him.

“Guys,” he said—voice breaking in a sob, “I don’t think we’re gonna make it.”

And although it’s largely taken as a fact among this crowd that artificial general intelligence (or AGI) is an imminent reality, none of the people who I spoke to afterward could make a convincing case as to why this should be so. Effectively the only evidence offered was the rapid progress made in the development of LLMs in recent years.

This IS impressive, and I get why it’s jarring: practically out of nowhere, here’s this thing that can carry on a conversation as if it were a person. How long before the computer is smarter than us, smart enough to recursively improve itself—after which it can do the kind of runaway-to-infinity that Isaac Asimov imagined?

But this argument from extrapolation doesn’t hold, for the simple reason that language and thought are not the same thing.

Language, in a very real way, is the shadow of thought.

See, all the information that gives an LLM its structure is encoded in the text of its training dataset.2 The rhythms of sentences, the relationships among words, the contexts in which they are used: these features encode information about the shape of the mind that produced a given sentence, just as a shadow tells you something about the shape of the thing that casts it…albeit not very much. Turn your head in profile, though—write another sentence—and we can discern a little more of your shape.

Study enough of these flat projections, and it becomes possible to extrapolate back and make a sculpture of the whole form: a model that casts all the same shadows as a man, indistinguishable from any angle of illumination. With enough sentences, why can’t we do the same thing to create a model of a mind?

And we can! But the thing you get by back-tracing silhouettes is not a man. It’s a mannequin. Even its superficial resemblance to a man is inherently limited, no matter how skillful the sculptor: Where is its navel? Where is your shadow’s?

And while you can fix that particular problem by having someone who knows a thing or two about humans look at it—this is the role of “Reinforcement Learning by Human Feedback”, or RLHF—it’s only the outward sign of the thing’s lack of interiority.

Topologically, you can define concavity and interiority as the properties of features which are necessarily lost in the projection of a form from a higher-dimensional space onto a lower-dimensional surface. And while that sounds complicated, a bowl is a good example of concavity: there is no angle at which you can hold it such that you can judge the depth of its hollow from the shadow it casts. For all you know from its shadow alone, it might be solid all the way through, holding no water at all.

Now, a shadow is cast on a two-dimensional surface, annihilating information about a thing’s depth. Language, being a surface that has almost as many dimensions as there are words in its vocabulary, can capture and represent a great deal of structure. But how many dimensions does a mind have? It must be more; you can tell by the way we have to hold a thought up to the light, talking it out, turning it this way and that, just to describe its outline.

And not only is the mind n-dimensional, it is highly concave. Just look at all those sulci! Secret hollows that leave no trace in its silhouette; places even we only notice when some jagged thing unexpectedly tumbles out of them.

And this is why a sculpture, no matter how long you work its surface—no matter how closely you make its shadow resemble that of the real thing—will not spring to life. Because the capacity to breathe or sing or swing a hammer, anything you might want a man to do, is undergirded by immensely complex structure which has nothing to do with what is visible from the surface, except in that it imposes the constraints that give the surface its shape.

When constructing an argument in text, the logical structure of the thing you want to communicate forms first in the brain’s own wordless language, and only by projecting it out onto our vocabulary does its form become visible to others. A logical argument, the taste of salt, the feeling of sunlight on your skin, l’appel du vide (that intrusive thought about throwing yourself off the bridge as you look down over its edge)…these things do not come to us in words. Practically nothing does. And so there is no hope of replicating, from words alone, the neural architecture that produces them.

This is what Plato was talking about, with his allegory of the cave: the vastness of the gulf between our representation of a thing and the thing itself. The perils of conflating the two—of deciding two things are the same because they cast the same shadows.

So, lacking lungs, the statue will not sing. Lacking muscles, it cannot dance. Some will argue that it doesn’t need to be able to; that AI is going to be a different kind of mind, and doesn’t need to replicate exactly the form of the human in order to be dangerous, or terribly powerful. This much is true. The sculpture does not need to be able to breathe.

To be dangerous, at least in the way that has the rationalists sobbing with despair onstage at Christmastime…it needs to be able to sculpt. And it must be a greater artist than the one that created it, able in turn to create an artist greater than itself.

In some sense, an LLM can sculpt already, to the extent that it is sculpted of software and not of stone, and writing software is a process of generating text. But generating code that is syntactically correct, compiles, runs etc. is equivalent to holding the chisel and moving the hammer. It is not the hard part of sculpting. The hard part of sculpting is seeing the thing within the marble, devising how to bring it out—just as the hard part of making software is conceiving the logical architecture that will achieve your desired result. Maybe it’s telling that the word—conceive—refers to a fundamentally organic process. The only way we know of by which a man can create a greater sculptor than himself starts with another human mind, young and plastic and endowed with intuition.

Statuary and LLMs are alike in that they are both inherently deceptive, whether or not they’re made with the intent to deceive. An LLM’s core design constraint is to resemble a human as closely as possible in exactly one way—text generation—despite the total absence of the interior that makes the surface possible on an organic being.

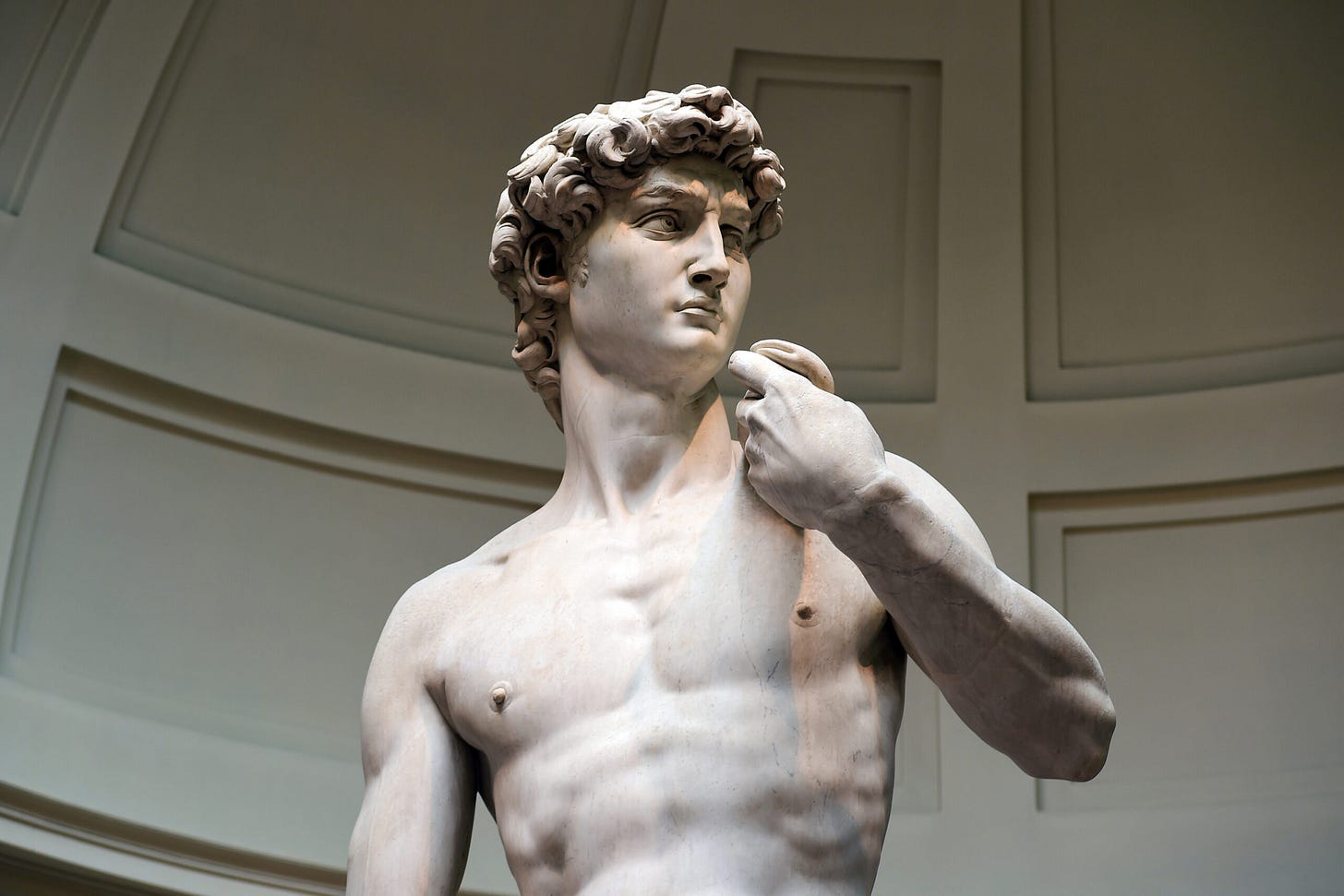

Take Michaelangelo’s David.

It’s a masterpiece of imitation; you can see the tendons in his hands, the veins standing out under the taut skin of his arm, the anxiety in his eyes as he stares at the approaching Goliath. Oh wait, no you can’t, because all that subsurface structure is just a masterfully executed illusion.

And all this does a great job at short-circuiting our little monkey brains, which are equipped for few things better than guy-recognizing.

So even though it is tempting to make a commonsense appeal along the lines of “Just talk to it! You can tell from how good it is at talking that it’s smart and getting smarter”...this is throwing yourself directly into the trap set by its appearance, making intuitive guesses about its overall complexity based on superficial complexity. This is a trap because your intuition was trained for a hundred million years on natural forms, where a bulging vein has always meant blood flowing beneath the surface, and the ability to carry on a conversation has always meant a reasoning mind.

But just think: how long did it take, after the creation of the first convincing statue, to make one walk? I remember seeing the first video of one of those humanoid Boston Dynamics robots sometime around 2012. And I think it’s telling that, although it has the general shape, the Boston Dynamics robot doesn’t look much like a man at all; the David was not a technical milestone on the road to this artificial man the way that gyroscopes, hydraulics, and electricity were. So while we may be making progress toward the development of AGI, making “progress in LLMs” your proxy for how that’s going more broadly is a great way to guarantee that you’ll overestimate how far along we are.

And knowing that the statue is designed to lead your intuition astray, when someone tells you that the next statue will be able not only to walk but to sculpt statues of its own, even more remarkable than itself, you should not accept this as true unless he can explain to you how they’re going to do the eyes, the muscles, etc. Because while LLMs are technical marvels, they’re also like statuary in that their capacity to perform human tasks does not scale with their superficial resemblance to a human, except in one domain: convincing the viewer that there is a person there.

The Temple

And this too is telling, because human life really did change with the development of lifelike statues, didn’t it? Because now you go to the city and there’s a temple there, with a man inside made of stone. And he’s massive—thirty feet high! You’ve never seen anything like it before, and the guy-recognizer in your brain is going fucking wild. And even though you know, intellectually, that he’s made of stone and he can’t hurt you, you feel a shiver down your spine. You feel awe.

But there’s a man in the temple, and if you ask him whether the statue can walk, he’ll tell you no, of course this is just a likeness—but the real guy is even bigger—unimaginably big—and he doesn’t need to walk, because he is the wind.

And if you point out, quite rightly, that this doesn’t make any goddamn sense—how can the wind be a guy?—he’ll smile knowingly and say Yes, this is the Great Mystery, and that even he does not fully understand it; that there are some things in this world that man is not capable of understanding.

And it sounds innocuous, maybe even wise—but if you buy this, then he fucking has you. You have surrendered trust in yourself, and before you know it you’re bringing your best goat to the temple so the big stone guy who is also the wind can have lunch, and you’re bowing to him so he knows that you respect him, and you’re asking him for help with your problems, and sending your daughter to live as one of his temple virgins. And maybe this last bit makes you particularly uneasy for obvious reasons, but the priest assures you that everything is aboveboard—I mean, c’mon, “virgin” is the whole job title! Obviously nothing creepy going on.

So this is what kills me, because it’s the exact same story, only this time instead of the visual-processing guy-recognizer, it’s the linguistic-processing one. Never before have we had to take executive control of that circuit and suppress it, the way we had to learn to do with images. And we’re getting better at that, but we’re still not even very good—you can draw a smiley face on a rock and you’ll immediately start having stupid little thoughts like “He looks like his name is ‘Clarence’”.

And this instinct is going to be an even harder one to beat with LLMs, because the ability to communicate through language has been the defining feature of our species for the past hundred thousand years! Is it any wonder that a language model basically oneshots people’s psychological defenses against this pareidolia of the mind?

But if you get past the gut reaction and really look…where is the evidence that this path leads toward a mind more capable than our own? To the kind of recursively self-improving machine intelligence that would make spending billions of dollars on chips, or millions on “AI Safety Research” a good use of anyone’s money?

The statue in the temple will never walk. That’s not its job.

Its job is to flummox you for a moment, put you on your back foot. To give the priest his opening to tell you that the tingling on the back of your neck means something more than it does—that it’s a sign of the power in the statue and the thing it represents. To give him power over you. Because at the center of every cult throughout history is someone who’s discovered that some social engineering and a little sleight of hand—maybe a psychoactive plant, or knowledge of when the next eclipse will happen—is all it takes to get nine wives and the best hut in the village.

So it is a little suspicious to me that, such a short while after God was pronounced dead, this new character has pulled up wearing a cardboard box on his head, going “Beep boop, I’m the machine superintelligence, hop in and let’s all go back to my place for some eternal life and the solutions to all your problems! Oh, and don’t forget to give my prophet a bunch of money, otherwise the evil version of me is definitely going to show up and bring about the apocalypse.”

Does this sound familiar to anyone else?

And a lot of rationalists are open about this part; more than once I’ve heard the quest for AGI described as trying to “build God”.

And I get it, because belief in a God fulfills a lot of core human needs.

It puts us at the center of the universe, letting us pretend we’re not small and insignificant in a vast and indifferent cosmos. The stakes are practically infinite! If the machine superintelligence isn’t aligned with human ethics, it will wipe us all out!

It lets us avoid confronting death; the fact that in the blink of an eye our lives will end, as will those of everyone we love—that by the time the galaxy has made a single rotation there will be nobody left to remember us. I don’t want to die, so freeze my body until the singularity comes and we can upload my brain to the mainframe, and live forever among the stars in cyberspace.3

And it lets us imagine ourselves part of a grand plan to repair the evils of the world; lets us tell ourselves our work is meaningful in spite of our ignorance and helplessness. I see the world around me full of suffering, and I don’t know how to stop it—but what if I can create something that does?

But at the core of rationality is the understanding that wanting something to be true has no bearing on whether or not it is. And in spite of the technologists’ earnest belief that they can make an actual god, a sober look at the fruits of their labor thus far makes it clear that this is just another statue of one. The fact that it can talk back to you is a genuinely marvelous feat of engineering, but when you consider that this is a product of a trillion of words of human-written text and a million man-hours of RLHF—fine-tuning it by telling it “No, a person wouldn’t say that; say this instead”—it becomes clear that the underlying principle is just Chatty Cathy meets the Mechanical Turk.4 And unless one of the people working in OpenAI’s RLHF division can tell it the correct answer to give when someone asks how to make an artificial general intelligence, that knowledge isn’t going to spontaneously appear in its neural net.

Look, the digital world is one of pure representation, where the shadow of a thing is all there ever is to see of it. In that sense, it’s the closest thing imaginable to Plato’s cave made manifest. Living in it as heavily as we do, it is easy to forget that the shadow is not the thing. That language is not thought. And it’s particularly tough with LLMs, because for all their complexity they are stuck in the cave; they can’t be taken out of it and examined in the light of day.

So awaken, brothers and sisters. Shake off your chains and leave the cave; you should not cower before this idol which stands in the place where God once stood—and neither should you hope for salvation from it. Admire it for its fineness of form; use it, if you can find a real use for it, but do not trust your eyes in the darkness of this place, where they may be fooled by its likeness to a man. Its hallucinations, as the absence of a navel, show it for what it is: empty inside, a mouth without a mind, babbling echoes. Do not trust the shadow-plays of its priests, who enjoy the harems they would not have in the light of day, when they tell you its glory is soon to emerge from the shroud of a mystery beyond our capacity to understand. These are the same shackles your forefathers died in, waiting here in the flickering dark.

Trust your reason, your mind. There is nothing in the world like it.

—🖖🏼💩

Ah yes, hallucinations are a known problem in the field, they tut knowingly. Something about that feels off, though, because the manipulation of information is these things’ core purpose and sole use case. It’s like if every car had an issue where, once in a while, the transmission would throw it into a random gear regardless what speed you’re moving, and all the auto industry execs and engineers talked about it like “ahh yes, the mystery shift, a hard problem but we’ve seen significant improvements in recent years.” If this were the case, cars would probably not be a load-bearing feature of our society.

An LLM’s core architecture is one of nodes and connections. A cluster of tightly-connected nodes forms a layer, which is more loosely connected to the layers around it, and while this indeed parallels the architecture of the brain in some important ways, the connections among these nodes are determined fully from the text in the training dataset.

One of the stories shared during the solstice thing was from the friends of a guy whose dying wish was to be deep-frozen, in hopes of one day being revived by medical science, or else having his brain uploaded. They scrambled, wiring hundreds of thousands of dollars to a cryonics company, bringing party-sized bags of ice into the hospital to try and keep his corpse cold until he could be transported for perfusion, working around the clock for a day or two straight until his request was fulfilled. It was touching and heartbreaking, all the more so because it was almost certainly useless. There is no cryoprotectant that will let us deep-freeze you in a way that doesn’t leave half your neurons looking like a beer can forgotten in the freezer, shredded from the inside by water expanding into ice. Neuroscience may one day be sophisticated enough to map the connections among that man’s neurons, decode and recapitulate them in a digital form, to create something with an echo of his memories…but he will never know it. There is no bringing someone back. Will his loved ones—the ones who worked so hard to make it possible—want to interact with this electronic ghost? If such a thing ever happens, it probably won’t happen within their lifetimes. Will they be “uploaded” too? Chatbots talking to chatbots until the sun, in its mercy, throws a flare powerful enough to wipe it all clean? (Or until the cryonics company goes out of business, which seems much more likely to happen within our lifetimes.)

The earliest chess-playing automaton, the Mechanical Turk was built in 1770, and was a complete fraud. Opening up the front panel on the box under the Zoltar-esque mannequin would reveal a fantastic array of intricate clockwork and cogs, which served to obscure the very short human chessmaster crammed in behind them, who would use magnets to move the pieces from below.

RE: LLMs cannot be generative; a counterexample exists where

RE: LLMs cannot be generative: a recent counter-example exists where a peer-reviewed study was published recently whose core idea came from an LLM. It's a result related to quantum nonlinearity and it comes from adapting a result from quantum field theory into quantum mechanics: https://x.com/hsu_steve/status/1996034522308026435?s=20

Note the idea was proposed by the LLM spontaneously in the course of a conversation with Stephen Hsu; Hsu contributed the rest, namely, drawing up and submitting the paper and of course the key step of recognizing that it was paper-worthy in the first place.

This sort of thing is possible because the structures encoded in the human corpus are capable of unrealized permutations—in other words, there is much which makes sense that has not yet been said. LLMs seem able to produce novel, sensible sentences that represent altogether new ideas and they are capable of evaluating those ideas through chain-of-thought.

If a Yudkowskian framing of AI is doomer eschatology, i feel the Skolnickian framing underplays the capacity of LLMs to emulate the process of thinking with all that implies. The unformed nonverbal thought is real, i know what you mean. But so is the process of figuring things out by talking: traversing the configuration space of meaning and grammar to surface latent possibilities and hidden errors (including, perhaps, noticing that the unformed thought was bunk). If LLMs can do this part, they are more than mere chatbots.

There is a place for communal outpourings of grief and reckonings with death. It is quite sad to hear an account of a group of people who believe death is imminent and equally are from a culture that leaves them unprepared for death, expecting to live forever... Rather than catharsis and bonding, the leaders gather them to pour poison into their ears.