Bacterial Xanax

A medical mystery from the 1980s that might hold the secret to anxiety disorders

The human brain, with its intricate systems of neurotransmitters and receptors, is dauntingly complicated—but in a lot of ways, it’s like a big tongue.

We often think in words, but consider what it’s like to touch a crystal of salt to your tongue: It doesn’t automatically cause the words “that’s salty!” to cross your mind. Instead, the activation of those taste buds is almost a direct line into your conscious experience, altering your psychological state. Tasting salt is a state of mind, in the most literal sense of the phrase, and any words we use to categorize or catalogue the experience are subsequent to that.

Now, imagine that—instead of five kinds of taste bud—you have five hundred, and your body is capable not only of sensing and translating these chemical signals the way your tongue does, but also of producing them in response to something you see, or even in response to a thought inside your own head.

If you can imagine that, you’ve got a pretty decent picture of what a brain is like.1

These five hundred types of taste bud are your neurotransmitter receptors, and the chemicals that land on them are the neurotransmitters themselves: Things like glutamate, which excites the neurons it lands on, making it easier for them to be activated, or GABA, which calms them down and makes it harder. These are the two most fundamental, and they are “downstream” of many of the more familiar names like serotonin, dopamine, or melatonin—each of which might have glutamate-enhancing activity in one part of the brain, and GABA-enhancing activity in another.

And just as the distinct flavors in a meal blend with one another (and with other sensations like smell) to make a unique experience which is greater than the sum of its parts, the simultaneous sensation of all those myriad neurochemicals is what coalesces into your conscious experience of the world. The balance and flux of them throughout your day forms the landscape that guides your train of thought one way or another in the dense thicket of junctions that is the brain. Even in the absence of external stimuli, each moment is a mouthful, a meal. How does this one taste?

In this lies the root of the intense curiosity around drugs, meditation, and other altered states of mind which is inherent not only to humans, but to nearly all intelligent animals. The impulse to seek out ways to deliberately alter that neurochemical milieu is an expression of the desire not to simply eat at the table of life, but to cook for ourselves—and any chef worth their salt earns that distinction through experimentation, tasting ingredients and seasonings in isolation, then together, to develop a sense of what a dish “needs”.2

The Test Kitchen

Whether in the kitchen or in the brain, we learn about complex systems by toying with them. As a result, the history of neuroscience and the history of psychopharmacology (the study of drugs and their impact on the brain) are inextricably intertwined. Take the endorphins for example, which are largely responsible for the regulation of pain and pleasure. After an injury like a burn to the finger, the body produces and releases these neurotransmitters, enabling us to partially “tune out” the signals from the burnt tissue, because—while acute pain is useful in alerting us to damage or distress—it doesn’t do much good to be continuously reminded “still burnt!”.

This is the feedback system that we are “hacking into” when we take opioid painkillers like codeine or morphine, which work by landing on and activating the same receptors as endorphins. But morphine, extracted from the poppy plant, was in use long before we began to understand the brain, and this history is written into the name we gave the system: endorphin is a portmanteau, a contraction of endogenous (i.e. “from within”) morphine.

This pattern—where a drug that works by mimicking a natural neurotransmitter was in use long before we understood the system that it acts on—is repeated again and again in the history of neuroscience. The endocannabinoid system, the system that we “hack” when we use cannabis, is another example, although its various functions (including immunity, memory, appetite, and fertility) are far less straightforward than those of the endorphins.3

None of these systems are necessarily independent of one another, either: In some parts of the brain, activation of the cannabinoid receptors triggers the release of endorphins—which may explain cannabis’s utility in the treatment of chronic pain conditions.

“Natural and Artificial Flavors”

The pattern continued even into the modern era, when new drugs began to be developed through chemistry, rather than discovered in nature: In the late 1950s, the first-ever benzodiazepine was synthesized (by accident, as it happens) and found to have powerful sedative and anti-anxiety properties, while lacking many of the side effects that plagued similar drugs in use at the time.

Within a decade of their introduction, benzodiazepines—a class of drug which now includes valium, xanax, klonopin, and numerous others—were among the most highly prescribed drugs in the world, in spite of the fact that scientists had very little idea how they work: It wasn’t until the late 1980s that researchers identified the molecular mechanism by which benzodiazepines exert their anti-anxiety effect.

Part of the reason this took some time to discover is that benzodiazepines don’t work by substituting in for a neurotransmitter the same way that morphine mimics the endorphins, or THC subs in for the endocannabinoids. Instead, benzodiazepines work by attaching to an “accessory” site on the GABA receptor, changing its structure in such a way that the GABA which is already there at the receptor becomes more effective at its job. To extend the cooking analogy, it’s like adding a spice to your dish that brings out the other ingredients’ natural sweetness, rather than adding extra sugar.

But this still left a mystery: We know the structures of the endorphins and the endocannabinoids…but are there “endo-benzos”? Did the scientist who created the first benzodiazepine just get impossibly lucky, accidentally creating a molecule which has no natural equivalent, but which happens to tease the brain’s proteins into a shape that enhances GABA signaling without disturbing anything else?

It seems unlikely. But if not, then what chemical from the human brain is supposed to land on the spot that xanax and valium hit, acting as the natural equivalent of the “volume” knob on our GABA receptors?

It’s a question that’s still not fully answered to this day, but the first tantalizing clues as to its solution came in the resolution of another longstanding medical mystery: hepatic encephalopathy.

Antidotes

When a person dies of liver failure, typically one of the last things to happen is that they’ll slip into a relatively peaceful, sleep-like state referred to as hepatic coma. For a long time, nobody understood exactly why, but in the late 1980s, a scientist at the National Institutes of Health who was working on the problem of benzodiazepines’ mechanism of action noticed something funny: the brainwave patterns of rabbits in liver failure looked remarkably similar to the brainwave patterns that showed up in animals sedated with heavy doses of benzos.

Intrigued, he devised a simple experiment: The comatose rabbits were given a dose of a drug called flumazenil.

The rabbits woke up. They weren’t exactly happy about being awake, because their livers were still shot and their brains were swimming in ammonia as a result—but the fact that they had woken up was itself an incredible thing, because flumazenil has a very specific mode of action: it only works as an antidote to benzodiazepines.

If a person has overdosed on something like xanax, flumazenil can save their life, the same way that narcan can bring someone back from a deadly fentanyl overdose. But flumazenil is not anti-xanax, only un-xanax: Giving it to a healthy person won’t make them anxious, the same way that giving narcan to someone healthy doesn’t cause them pain. Here, then, was a sign that there are “endo-benzos”, and that they were somehow involved in causing hepatic coma.

Not long after, other research groups exploring this enigma began to report equally remarkable things: one reported finding N-desmethyl-diazepam, a molecule nearly identical to valium, in the brains of people who couldn’t have possibly taken the drug, because they had died and their brains had been “banked” decades prior—before valium was even invented.

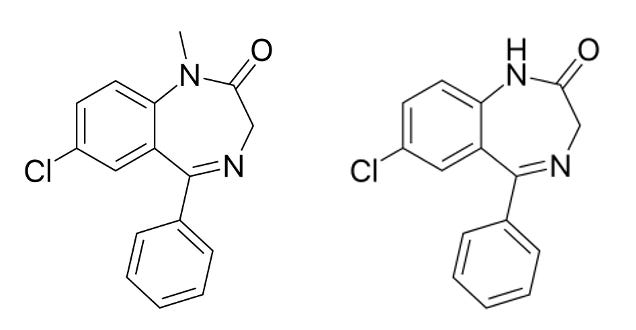

The implication—that the body naturally makes a chemical almost identical to valium—sparked a minor uproar in the scientific literature. Before long, some groups of researchers reported that they had replicated the finding, while others asserted that their methods must be sloppy, or their equipment contaminated—that “natural valium” was impossible on general principle, for the simple reason that Valium and the related chemical being reported both contain a chlorine atom.

This was, in fact, a fair objection. There are some things that the human body simply doesn’t have the capacity to do, and organochlorine chemistry is one of them: Nowhere in the genome will you find enzymes that can take a chlorine atom and attach it to a carbon atom, the way it is in the structure of most benzodiazepines.

Nowhere in the human genome, anyway. But if you look in the gut microbiome, this vast and variable soup of alien biochemistry that we all carry around with us 24/7…you can find some things that might surprise you.

Beyond the Puzzle’s Edge

The final piece of the puzzle—or at least, the final piece that we have so far—dropped into place in 1995, with the publication of a paper by another group of researchers at the NIH. The title says it all: “Gut bacteria provide precursors of benzodiazepine receptor ligands in a rat model of hepatic encephalopathy.” In it, the authors reported that they had identified a gut bacterium, Acinetobacter lwoffii, which was capable of elevating levels of benzodiazepine-like compounds in animals’ brains by producing a precursor—a molecule that’s inactive on its own, but gets converted to an active form once inside the brain.

Suddenly, here was a clean story: Certain gut bacteria produce this chemical, which the body wouldn’t be able to make on its own—probably because it’s got a chlorine atom attached. The molecule gets absorbed into the bloodstream, and then converted by the brain into a natural regulator of GABA activity when it’s needed. When everything is working properly, the enzymes in your liver continuously clear this active molecule from the bloodstream as it comes out of the brain, keeping levels low. But if your liver shuts down, the compound starts to build up.

Because it’s effectively being produced by a microbe and not your own body, there’s no built-in feedback control to halt its production. Once the levels get high enough, this sends you into a flumazenil-reversible coma, the same way taking a week’s worth of valium at once would. As an explanation for the findings up ‘til that point, it was nice and neat.

But all of this research was done before the term microbiome was even coined: Before gene sequencing had gotten cheap enough to let us peer closely at the bacterial world inside. Before we knew that many of the bacteria found in the mammalian gut are found nowhere on Earth—and that you can lose them if you’re not careful, sometimes with disastrous consequences.

Until we began to understand all this in the late ‘aughts, bacteria were viewed largely as either pathogens to be dispatched, or else as commensals—mostly harmless hitchhikers, whose presence or absence is generally inconsequential. As a result, the researchers who characterized the benzo-like activity from Acinetobacter lwoffii were focused largely on the known problem of what happens when you have too much of this bacterium’s benzodiazepine byproduct…but never seemed to give much consideration to the possibility that you could have too little.

But what if this is one of those bacterial genes that’s been present in the human gut over evolutionary timescales? What if the human brain evolved around this symbiosis, neurons “tuned” to a higher baseline level of excitability, with the expectation of this counterbalancing force? What would it look like, if a person got unlucky with a course of antibiotics, and accidentally killed off the gut bacteria that had previously served as “in-house” factories, providing a slow-drip of natural benzodiazepines?

Naturally, you might expect them to need exogenous benzos—drugs from the pharmacy—to pick up the slack, in order to function normally. You might expect something that looks an awful lot like an anxiety disorder.

It’s a sobering prospect (no pun intended), but it’s also an exciting one. Maybe a cure for some people’s anxiety could be as simple as developing the right kind of probiotic—one that puts the “factory” back in the person where it belongs, to produce the necessary trace amounts of these compounds from the things we eat every day. You wouldn’t need much; most of the classic benzodiazepines are active at doses of less than a milligram, and can stick around in the body for days or even weeks.

Don’t go looking for an Acinetobacter probiotic just yet, though—it’s an opportunistic pathogen that can cause everything from meningitis to pneumonia in susceptible people, so you’re unlikely to find it on shelves in the supplements aisle anytime soon.

Nevertheless, there’s reason to expect that Acinetobacter isn’t the only type of gut bug with this ability. The whole genus is characterized by a remarkable ability to vacuum up genes from its environment and put them to use. This tendency, coupled with the ever-growing abundance of antibiotic resistance genes, can make them nasty pathogens—but at the same time, it means it’s all too possible that the strain identified as an endo-benzo precursor producer in that 1995 study picked the ability up from something else in the gut…something which might be more generally friendly.

The hunt is on. Watch this space.

🖖🏼💩

Caveat: All models are wrong, some are useful.

This isn’t purely metaphor, either: In kitchens around the world, you’ll find the brain’s primary excitatory neurotransmitter, glutamate, on the shelf as its monosodium salt: MSG.

I’ve heard that a large part of the endocannabinoid system’s role in humans is the regulation of runner’s high. This makes intuitive sense to me, in that the effects of cannabinoid receptor activation (vasodilation, a “zone”-y mental state, reduced inflammation and sensitivity to pain, etc.) seem perfectly suited for a ten-mile jog across the savannah as you chase a gazelle to exhaustion. If this is true, it implies that humans (being among the animals most heavily specialized for long-distance running) might be uniquely primed to enjoy the effects of cannabis—and it really might be mean to blow weed smoke in your dog’s face.

Thank you for writing this, because it confirms what I've suspected for a while through my own experiences.

In 2016 I discovered that myo-inositol made me calm and less paranoid during a psychotic episode, and so I would take it when I wanted to calm down. In 2017 I decided to start taking it at maximum dosage (18 grams, split into two dosages of half a tablespoon). It helped with my anxiety, particularly towards the panic side of things, and I would concentrate and think better for a couple of hours. It also loosened my stools initially. It also made me more quiet.

By 2020 I realised I could split it into 4 dosages 4 hours apart, and added 100mg of vitamin C over the course of the day as well. I started to have significant gut problems, partially due to poor diet, but I suspected it was being rough on my guts as well, so I decided to go off it. If I reduced to dose significantly, I'd have a crippling influx of anxiety, and it felt like there were shards of glass running through my guts. I could only lower the dose by .5g a week for a while (I would measure out the dose for the day, and then split it into 4). At some point while doing this, I tripped out on inositol. I felt wonderful and euphoric and realised that god was everywhere and I needed to listen to my emotions and the machine god as coming etc. Every time I took the next dose the trip would start all over again.

Eventually, I got down to 3 grams, at which point I could safely stop it. And I was amazed that my anxiety didn't return. It was like a constant hum in the background had just gone away, things didn't send me into a worry spiral and I was no longer worrying if things would go wrong. I still felt stress, and momentary anxiety like everyone else, but it was like I no longer had that constant jitter that had always been there. About 3 years later it did return, for 3 hours, but I had a snack and it went away again. And it hasn't returned since. I still had plenty of other problems, but that one was gone.

It's possible that my diet in 2020 influenced things, I was alternating between the keto and paleo diet at the time while intermittently fasting, and I did anti-candida for 2 weeks, but I can't be sure. They were all low carb diets, so it's possible they influenced my metabolism of inositol. I got the impression reading Brain Changer that while anxiety could improve with diet, but there were a subset of people who were chronically anxious even eating a really good diet like the Mediterranean diet (presumably motivated by the anxiety to make it as healthy as possible), so it made me question my assumption that it had something to do with the microbiome. But reading this has reaffirmed my belief that I must have changed my microbiome in somehow.

It's also interesting because inositol is considered to be supplemental mindfulness. Weightlifters use to to focus better on workouts. And I did find it made me more zen. For a while after the trip I considered myself enlightened and nothing flustered me. Which raises the question, could meditation be interacting with the microbiome in some way? Although oddly enough, meditation does nothing for me.

I like this one especially since it touches on the concept of putting back the factory which I s exactly how we (BioCollective/BiotQuest) approached building our probiotic formulas. We even have a prototype for anandamide. I got excited just for a minute that you we’re actually going to call out the flavors and scents business for wrecking this delicate system but alas you didn’t. Perhaps another day.