I keep saying that most of the dietary advice you derive from learning about the microbiome turns out to be things you already knew. Conventional wisdom. Eat lots of fresh fruits and vegetables, avoid processed foods, etc.

By and large, this advice tends to be hard to implement: Organic food is expensive, and resisting the temptation of sugary snacks goes directly against some of the body’s most hard-wired instructions.

But today it’s time for one of those rare tips, a simple thing you can do to improve your health via the microbiome, that you likely just didn’t know about. It’s called nattō.

Natto is a style of fermented soybean, but it’s completely unlike tempeh, tofu, and…pretty much every other food on Earth. Yogurt, kefir, pickles,1 and kimchi are fermented by Lactobacilli, while tempeh, miso, etc. are fermented by fungi—but natto is in a class all its own, produced by inoculating cooked soybeans with a bacterium called Bacillus subtilis.

Natto is a hidden gem of Japanese culture, and you can probably tell from the image above why it’s stayed hidden: the texture takes some getting used to. The beans are left whole, and the coating they develop during fermentation is somewhere between “sticky”, “slimy”, and “stringy”. Still, it’s been consumed in Japan for close to 1000 years and 85% of the country’s population eats it on a regular basis, so you can probably manage it. (I’m not a fan of indiscriminately applying the “efficient market” hypothesis to human behavior, but if that many people have been doing something weird and sorta gross for that long, there’s probably a good reason.) Besides, it’s actually delicious if you know how to prepare it, and it’s a biochemical powerhouse of health benefits—so let’s dig into a few reasons why, and then how you should subject yourself to the slimy spider-beans.

The Why

1. Pyrroloquinoline Quinone

…or PQQ, for short, because natto is already enough of a mouthful.

PQQ is a molecule with a colorful history. It acquired a bit of a reputation a few years back, when some scientists declared it to be a new vitamin. This kicked off a lot of scientific debate which hasn’t really been settled yet, but consensus seems to be coming down on the side of “helpful, but not really essential”.

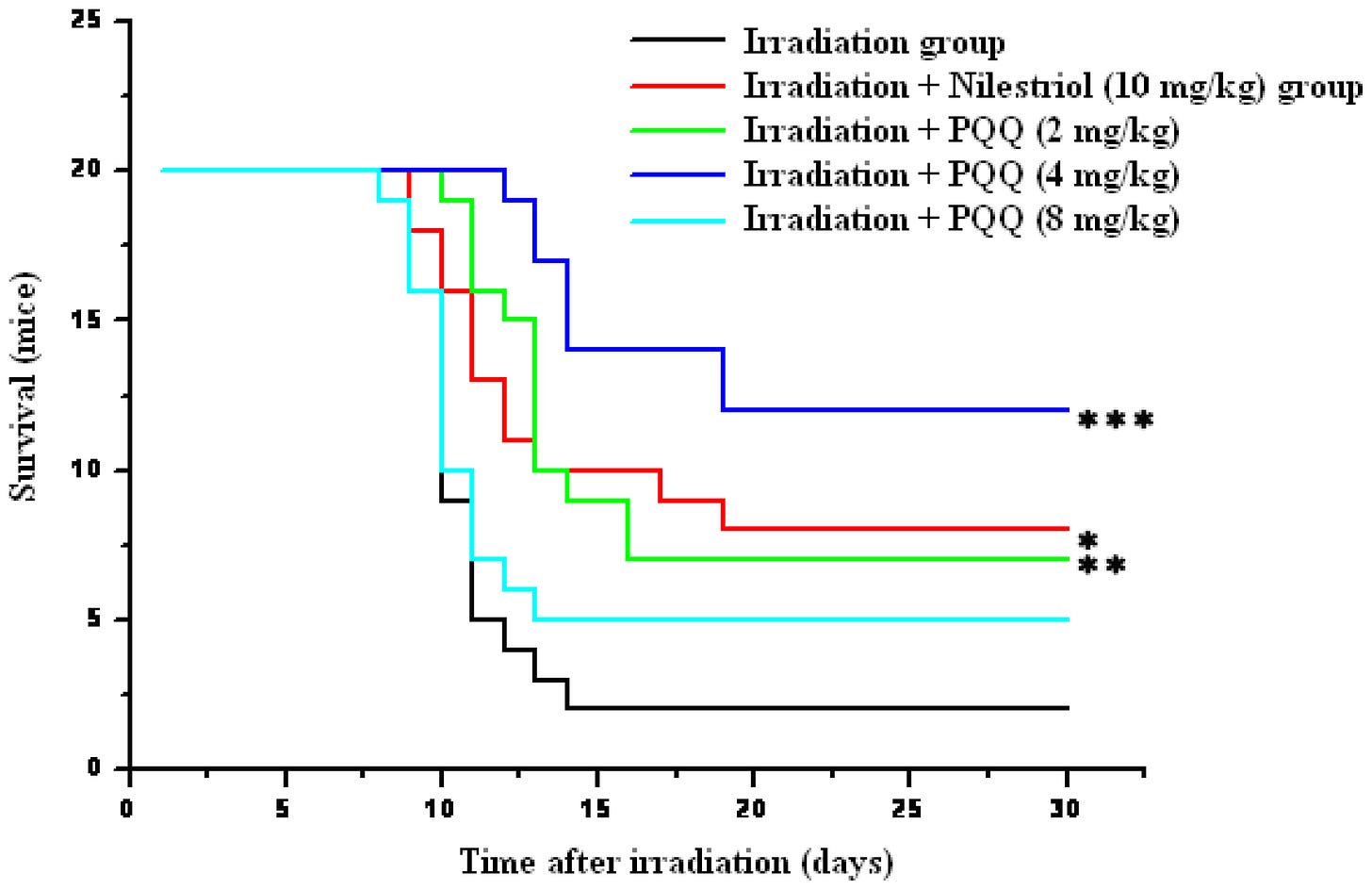

Still, it does have some interesting properties: bacteria like B. subtilis (and some gut microbes) make it because it helps them shuffle electrons around to generate energy, and it seems to provide a general buffer against stress in our cells. Animal studies found it to be cardioprotective, neuroprotective in hypoxia, and even protective against an 8 Gray dose of radiation.

If you skipped radiation biophysics in college, 8 Gy is the kind of dose where you had better start setting your affairs in order, because half your chromosomes are already unraveling at the molecular level like a skein of yarn hit by a shotgun blast and you have about two weeks before your cells decide, one by one, to give up the ghost.

Now, the usual caveat when making inferences about health effects from animal studies on minor food components is that you have to do the math. 4 mg/kg, or ~280 milligrams for a guy of average build, is a lot of this molecule, relatively speaking. In a pack of natto, you’ll find maybe 6 micrograms of PQQ, and 280mg is ~47,000 times that amount.

But the caveat to the caveat is that you're also not facing 8 Gy doses of radiation on a regular basis. I crunched the numbers, and it turns out that 8 Gray is about 470,000 times your average daily dose of ionizing radiation.

In studies like this, the point isn't necessarily to test things under realistic conditions of use—it’s to create a version of the interaction so exaggerated that you can see if your intervention has an effect within two weeks, rather than doing a 50-year cohort study of cancer incidence among natto eaters, where your participants do data-confounding things like smoke cigarettes and then lie to you about it. Much easier to just blast the mice and count the bodies.

I'm not going to pretend we can extrapolate linearly here, but the point is that—while eating the beans won't give you gamma-hardened superpowers—it might give you a modicum of extra protection against the kind of harms we all encounter in daily life. Not superpowers, but regular powers are good enough.

The added benefit—not just with PQQ, but with everything on this list—is that you end up getting more than what’s in the tin, because bacterial spores can survive the stomach, and continue to multiply and produce metabolites as they travel through your GI tract. The gift keeps on giving.

I wouldn't advise taking the kind of doses used in that radiation study just for fun, not least because mice tend to have a mg/kg tox tolerance about 12x a human's.2 Taking a large dose of PQQ is also likely a great way to selectively feed certain bacteria in your gut. That could be good, or disastrous depending whether you're harboring a latent pathogen that uses PQQ as part of its electron transport chain. It's not that cheap, either; a 280mg regimen would cost something like $8 a day.

Still, I keep a bottle in the cupboard. If the nukes start flying in our lifetimes, eight bucks to triple your odds of survival is a pretty good deal. In the meantime, I eat the beans.

2. Phytase

Seeds are like plant eggs. They’re the perfect starter kit for life, designed to give a fledgling organism all the essentials that it needs in order to put down roots, meet some rhizobacteria, and figure out the whole photosynthesis thing. They’re nutritious by design, which is why they’ve become the foundation of every agricultural society on Earth.

Plants, however, have never been happy with this arrangement where we eat their little ones.3 Over billions of years, evolution has favored plants that could provide nutrients to their young while discouraging interlopers like us from making a snack out of them. This pressure has produced an amazing variety of strategies, ranging in creativity from the coconut ("very hard to open") to the kidney bean ("contains a protein that glues your red blood cells together unless you cook it first”).

One of the more ubiquitous and ancient of these defense mechanisms is a molecule called phytic acid.

Phytic acid is the way plant seeds, from rice to wheat to beans, store phosphorous. Phosphorous is something that all living things need a lot of: it makes up the backbone of DNA and RNA, the “rails” of the twisted ladder that is a double helix.

So this is how plants try to keep us from getting our hands on their phosphorous: phytic acid is the “coconut” strategy applied on a molecular level—very hard to open. On their own, animals don’t have the enzymes to break the molecule down, so it passes through the GI tract undigested. And not only is it non-nutritious, it can act as an anti-nutrient: that dreamcatcher-like structure lets it trap a variety of minerals from the gut, keeping you from absorbing calcium, magnesium, iron, and zinc.

Although it’s not overtly toxic in the way that a raw kidney bean is, phytic acid was a big development in the early days of the evolutionary arms race between plants and animals. Cooking can denature a fraction of the phytic acid in seeds, but as we’ve talked about before, bacteria are our greatest weapons in that arms race: ruminant animals, which have gone all-in on the strategy of symbiosis by basically evolving into walking fermentation kegs, can digest phytic acid just fine with the help of rumen-bacterial enzymes called phytases.

If you hadn’t guessed yet, Bacillus subtilis produces a phytase enzyme too, meaning that a lot of the phytic acid in soybeans is broken down as they’re fermented into natto. Not only does this make natto more nutritious than unfermented soybeans, it makes other foods you eat it with more nutritious as well. Natto is typically eaten with rice, which allows the spores of B. subtilis that survive your stomach to get to work on the rice’s phytic acid in your intestines, breaking it down and making both the phosphorous and minerals available to your cells.

3. Vitamin K

Natto is one of the highest-vitamin K foods on Earth. We’ve talked previously about how bacteria contribute to the body’s supply of vitamin K—to such a great extent that, even in the absence of a dietary supply, a healthy microbiome is enough to prevent the blood clotting disorder that happens when you’re vitamin K deficient.

But regulating clotting isn’t vitamin K’s only role in the body; VK works by helping activate twenty or so different proteins that perform a huge array of functions. One helps limit calcium buildup on your artery walls. Another facilitates the perpetual process of bone remodeling, preventing things like fractures and bone spurs. Still another VK-dependent protein ferries thyroid hormones into the brain. A Dutch study in 2017 found vitamin K insufficiency in 1 out of 3 older adults, and a more recent study showed that hospitalized COVID-19 patients had significantly worse vitamin K status than controls, and that severity of vitamin K deficiency was associated with likelihood of being put on a ventilator.

The most common source of dietary vitamin K is leafy greens, but plants contain a form of vitamin K called phylloquinone—vitamin K1. This is different from the kind produced by bacteria, menaquinone: K2.

One of the key differences is that vitamin K1 has a hard time getting past the liver and into circulation; the bioavailability is about 1/10th that of K2, and the half-life in circulation is about 1/25th as long. The differences between plant-derived vitamin K and microbial vitamin K are so stark that some experts are agitating for public health agencies to issue separate “recommended daily intake” levels for K2, independent of K1.

Unfortunately, some of the people who need the benefits of vitamin K the most are given a specific medical mandate to avoid it. The popular “blood thinner” warfarin is basically anti-vitamin K, widely used under the logic that coagulation factors need VK to work, and it’s a lot harder to have a stroke or a heart attack if your blood can’t clot.

Warfarin is, to put it frankly, a shitty drug. It works well for preventing heart attacks, but it makes all your other vitamin-K dependent proteins stop working too, so the calcium slowly dissolves out of your bones and accumulates on the inside of your blood vessels instead. And because it works by keeping you in a constant state of VK deficiency, you have to limit your intake of leafy greens and fermented foods, and constantly monitor your blood’s clotting rate to see if your dosage needs adjusting. This is a shame, because many people with heart disease are also in the high-risk groups for things like COVID and osteoporosis, and—while I’m sure some patients love having the excuse of a “strict no-salad rule, doctor’s orders”—it isn’t good for you.

There are newer blood thinners out there, like rivaroxaban, which goes after one of the specific clotting factors rather than the whole K-dependent protein family. This seems clever! That’s not necessarily a good thing; half the time, very clever solutions just mess things up in new and exciting ways. Still, warfarin got its start as a rat poison, so with the standard of care being “what if you ate just a liiiittle rat poison?” we could probably do with a smidge more cleverness.

All this to say: if you’re on warfarin/coumadin, you should check with your doctor before incorporating natto into your diet—but you might also want to try and find an alternative to warfarin.

4. Nattokinase

Wow, what are the odds? Turns out B. subtilis also produces a fibrinolytic: a soluble enzyme that chews up blood clots. I’m a little more skeptical of the literature around this one than the others—phytase can act in the GI tract, but typically you don’t expect something as large as a functional enzyme to make it into the bloodstream. Enzymes are proteins, after all, and your gut is full of things that break down proteins.

Still, there are a couple of studies in both animals and humans showing that the enzyme reduces coagulation activity when taken orally, and bacteria have all kinds of neat ways of packaging things for protection, so it seems plausbile.

5. Iturin: The Fungus Buster

Candida is a nasty fungus. It’s best known for causing oral thrush and vaginal yeast infections, but it can also establish in your gut, which is apparently absolute hell.4 Typically, that kind of thing is prevented by competition from your gut bacteria, but antibiotics can leave you susceptible, and once an organism like that gets a foothold it can be very difficult to get out, even with antifungal drugs.

The trouble with fungi is that their biology is a lot like ours, so the drugs that kill them are often toxic to human cells too. Treat someone with an oral antifungal at the concentrations you’d need in order to firebomb the yeast out of existence, and you’re liable to do so much collateral damage that the cure would be worse than the disease.

But where oral antifungals are a messy carpet-bombing campaign, natto is like deploying ground troops. They’re well-armed, with molecular weapons like iturin and surfactin, which help kill Candida by dissolving fungal cell membranes. It’s worth noting that, like other antifungals, these chemicals can have activity against human cells too—but because they’re deployed on-the-spot, they reach toxic concentrations only in the microbes’ immediate vicinity.

I could go on all day (wait, come back, we haven’t even talked about ligustrazine yet!) but hopefully by now you’re convinced that Bacillus subtilis is worth a try. Whenever I tell people about natto, one of the first questions is usually “couldn’t I just take a Bacillus subtilis-based probiotic instead?”

These exist, but the problem is one of numbers. Natto absolutely blows probiotics out of the water: it contains roughly five billion CFU of bacteria per gram, where most probiotics hover around 3 billion CFU per capsule. A standard serving of natto is about 45 grams, so unless you want to take an entire bottle of probiotic pills every day, there’s no comparison.

With that, let’s get to:

The How

Step one is to find some natto. This will require an adventure to the nearest asian grocery store. The only other place I’ve seen it stocked is at some of the more avant-garde health food places. DO NOT buy it there; they’ll charge you $12 a jar, which is absolutely criminal. Natto is supposed to be good protein for the broke; $4 to $5 for a three-pack of the single-serve styrofoam trays.

It’s in the freezer section, you might need to ask a shop attendant for help since the labels often aren’t in English. Get the organic version if they have it. While you’re there, pick up a bag of rice, some good soy sauce (Ohsawa’s Nama Shoyu is the best I’ve ever had), and green onions. Maybe chopsticks, if you don’t have ‘em. Stash the natto in the fridge at home, so it can thaw; it’ll keep indefinitely in the freezer, but starts to dry out after a week or so in the fridge. You can use it frozen if you’re impatient, as long as the rice is hot.

Step 2: Make some natto rice. Cook up a pot of rice; while it’s going, slice a green onion thin, and fry an egg. Dish the rice into a bowl. Open one of the natto trays, peel off the film, and throw away the little plastic sauce packets that come with it.

(Optional Step 2.1: Use chopsticks to stir the beans around in the tray, sixty times. A Japanese person told me this is to “awaken” the natto and, while I have no idea what that means, there’s probably a reason.)

Mix the natto into the bowl of rice. Add a little bit of soy sauce and stir it all in, top with the fried egg and green onion. I put a squirt of sriracha or mustard in the corner of the bowl.

Step 3: Enjoy! There will be some cobweb-like strands of biofilm; you will learn to love them—or at least to grudgingly accept them as the price of a cheap, easy meal that helps you operate at your best.

—🖖🏼💩

A *proper* pickle will have only three main ingredients: cucumbers, salt water, and spices. Anybody putting vinegar in the mix is cheating.

Here’s how it’s supposed to work: Salt in the brine draws the sugar out of the cucumber and into the water. Lactobacilli that naturally live on the surface of the cucumber eat this sugar, turning it into lactic acid. This gives the pickle its tang, and preserves the product—this is also how kimchi is made. Most Americans have literally never eaten a proper pickle the way God intended, so Vlasic etc. get away with selling you salt-and-vinegar cucumbers that don’t have any of the probiotic benefits. The only brand I’ve found that’s an actual ~fermented food~ is called Bubbie’s; it’s in the refrigerated section at most grocery stores.

The growing accessibility of preclinical research reports has spawned a generation of self-styled biohackers, experimenting on themselves with new compounds, extracts, peptides based on one or two promising studies in animals. If you are one of these guys, Rule #1 is to know your allometric species scaling factors for toxicity. Actually, Rule #1 is “Cut it out, you’re not as clever as you think you are,” but Rule #2 is “If you’re going to anyway, print out that table and stick it up somewhere.”

Fruits are, of course, a notable exception.

A friend of mine had a years-long case of intestinal Candida infection, bad enough that eating any carbohydrate would have him doubled over in pain and laid up for days feeling like garbage. He’s cured, now—more on that another time.

i gotta say, this newsletter has far exceeded my expectations from when i initially subscribed. keep doin what ur doin

Stephen: Hello from Pepper Pike, Ohio. I believe N.R., my daughter, told you that I had found your natto article, which article I found to be well-written and researched, as well as entertaining. I have been taking powdered natto for several years, a couple of teaspoons a day. I have read a number of scientific studies on natto. One referred to the bacteria as "Bacillus subtilis natto", all in italics. Other articles just used Bacillus subtilis. As an aside, I got a B.S. from Indiana University, Bloomington, and worked for 5 years at St. Vincent's Hospital in Indianapolis in the mid-70s in their microbiology department -- all has changed. I've read a couple of books by Tim Spector and find the subject of gut health most interesting. I'll be reading the rest of your articles. Thank you. Linda Standish